This blog symposium, and the project it is part of, are revisiting a number of judgments of the European Court of Human Rights through an intersectional lens. Such effort, which requires looking at jurisprudence of the Strasbourg court in a creative way, could contribute to ensuring a protection of human rights that is much more integrative of the complex and multifaceted identity of every individual who approaches the court seeking justice, and one that is better able to assess how certain power structures may lead to differentiated forms of oppression.

Human rights bodies and courts at the supranational level have increasingly (albeit timidly) engaged with the notion of intersectionality, in an attempt to transcend the siloed approach that the definition of specific human rights has entailed for decades. Examples are the UN Women Intersectionality Resource Guide and Toolkit and the separate opinion by Perez Manrique in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights decision in Manuela et al. v El Salvador of 2021. Yet, that remains the exception, rather than the rule, with intersectionality addressed at the margins in most cases. The Court has not yet engaged with intersectionality in an explicit way. This post contends that despite the lack of explicit engagement with it, applying an intersectional lens to human rights protection is simply the most natural consequence of the interpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The current state of affairs

While several UN treaty bodies have referred to intersectional realities or applied an intersectional lens in their work (e.g. CERD General Recommendation No. 32, 2009, §7; CEDAW General Recommendation No. 32, 2014, §6; CRC General Comment No. 11, 2009, §29; CESCR General Comment No. 20, 2009, §17, 27), the Court’s engagement with the notion of intersectionality has been very limited, and where it has happened, has not been explicit. As this blog symposium illustrates, most Court cases do not acknowledge the complexity that an applicant’s intersectional identity brings to the case.

There are some cases that could be seen as engaging with intersectionality in some way, even if not expressly using the term. In Opuz v. Turkey, a case concerning intimate partner violence, the Court acknowledged that ‘Women from vulnerable groups, such as those from low-income families or who are fleeing conflict or natural disasters, are particularly at risk’ (Opuz v. Turkey, 2009, §99). In BS v. Spain, a case concerning a Nigerian woman working as a sex worker in Spain who had been assaulted and racially abused by Spanish police officers, the Court determined that the Spanish Courts did not consider the woman’s ‘particular vulnerability inherent in her situation as an African woman working in prostitution’ (B.S. v. Spain, 2012, §62). As Bond has flagged, this was ‘the first time the Court expressed a willingness to consider intersecting forms of discrimination’ (Bond 2021, 122). In Garib v. The Netherlands, a case concerning housing discrimination, the dissenting opinion of Judge Pinto de Albuquerque called for the Court to ‘reach a global and comprehensive understanding of the various discrimination situations’ to ‘guarantee the effectiveness of the convention rights’, while observing the fact that Ms Garib was an impoverished woman increased her vulnerability in the context of the Dutch housing policy (Garib v. The Netherlands, 2017, Dissenting Opinion of Judge Pinto de Albuquerque joined by Judge Vehabović §34).

Yet, in these cases the Court has used an additive notion, of ‘particular vulnerability’, rather than opting for an explicit use of intersectionality. This additive approach, which as explained below may result in an oversimplification of complex individual realities, considers various forms of vulnerability or discrimination in parallel, but fails to integrate how each of those factors influence each other.

This is very much in line with the limited intersectional approach in international human rights law more generally (De Beco 2017), where levels of engagement with intersectionality across and within human rights bodies and courts remain uneven, unpredictable, and often non-explicit (La Barbera and Lopez 2019).

The notion of intersectionality has been given multiple definitions in different contexts, and the lack of a clear definition has resulted in a resistance by some actors in the legal and policy spheres, as the implications of its use are not always clear. Yet, not engaging more explicitly with the notion is also a missed opportunity, as intersectionality allows a court or human rights body to explore the implications of an intersectional identity on the effective enjoyment of rights, beyond the juxtaposition of various vulnerability factors.

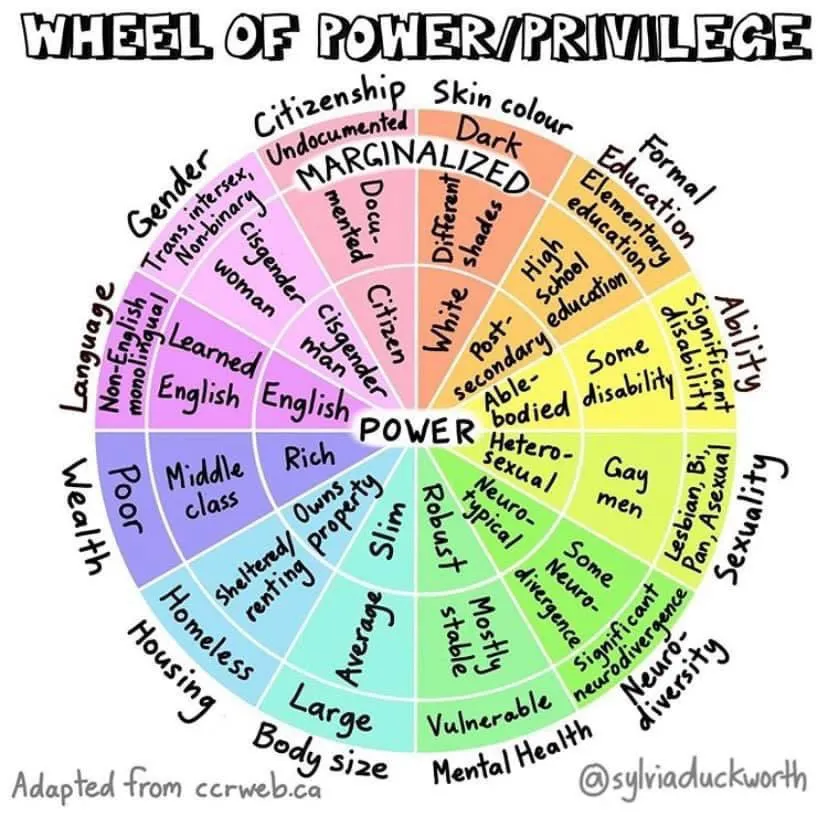

The multiple combinations in which the categories of the wheel of power and privilege can be presented demonstrates a palette of identities that cannot be fairly encapsulated by the notion of ’particular vulnerability’. In addition, focusing on vulnerability can increase the sense of victimhood, deplete agency, and limit the recognition of ‘the systems of subordination that intersect to harm victims’ (Bond 2021, p. 127). Human rights courts and bodies need the space or margin of appreciation to articulate how the specific combination of identities in a specific case have affected the victim’s enjoyment of their rights.

It is critical to understand how the multiple facets of individuals intersect and to tackle any systemic imbalances in human rights protection. Only then will such a system be able to protect and facilitate the right of the 8 billion individuals in the world to a ‘life with meaning’, a ‘life with dignity’, which is required, according to the UN Human Rights Committee, to guarantee the right to life (HRC General Comment No. 36, 2019, §3). Only then will the Court be able to guarantee a fully effective protection and enjoyment of Convention rights.

Anchors to intersectionality in the European Convention

The good news is that a close look at the European Convention shows that its text already provides the necessary anchors for intersectionality, based on which the Court is able to take the creative and progressive approach that this symposium and project propose, ensuring such fully effective protection of Convention rights. This is possible relying on the principles of interpretation of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, in particular on the ordinary meaning and the object and purpose of the Convention (Art. 31). There are two main anchor points for intersectionality in the Convention: the right to an effective remedy (Art. 13) and the prohibition of discrimination (Art. 14 and Protocol No. 12).

Under Art. 13 of the Convention, everyone has the right to an effective remedy, which means that individuals can obtain relief at national level for violations of their Convention rights, before using the regional and international protections available (ECHR guide on Art. 13, p. 7, referring to Kudła v. Poland, 2000, §152). States are given a margin of appreciation as to how to provide an adequate avenue for remedy (ECHR guide on Art. 13, p. 14, referring to Kaya v. Turkey, 1998, §106), which depends very much on the right at stake (ECHR guide on Art. 13, p. 14, referring to Budayeva and Others v. Russia, 2008, §191). Should the domestic authority’s remedy fail ‘to take into consideration an essential element of the alleged violation of the Convention, the remedy will be insufficient’ (ECHR guide on Art. 13, p. 14, referring to Glas Nadezhda EOOD and Elenkov v. Bulgaria, 2007, § 69). If an individual affected by a Convention right violation is someone with an intersectional identity which is affecting their enjoyment of such right, a remedy not considering how the various aspects of their identity have intersected and made their situation particular towards the enjoyment of such rights would clearly render such remedy insufficient.

The other clear anchor to intersectionality in the Convention is the prohibition of discrimination. Under Art. 14, the enjoyment of Convention rights ‘shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status’. Complementing this provision, Art. 1 of Protocol 12 to the Convention enshrines a general prohibition of discrimination, prohibiting discrimination in the enjoyment of any right set forth by law, beyond Convention rights.

As the guide to Art. 14 and Protocol 12 clarifies, ‘in cases concerning discrimination through violence emanating either from State agents or private individuals, State authorities have been required to conduct an effective and adequate investigation by ascertaining (…) whether feelings of hatred or prejudice based on an individual’s personal characteristic played a role in the events’ (ECHR guide on Art. 14 and art. 1 of Protocol 12, p. 9). This reference to the individual’s personal characteristic could be the basis for an intersectional approach to the protection of Convention rights more broadly. Although the cases where this was required from State authorities considered only one discrimination ground (Abdu v. Bulgaria, 2014, § 44; Milanović v. Serbia, 2010, § 96-97), considering the characteristics of an individual is a complex task that cannot be completed without a holistic approach to their identity, which is what intersectionality ultimately is about.

Concluding remarks

Calls for an intersectional approach in human rights law and courts, including the European Court of Human Rights, seem to come as an innovation, which one could associate, in terms of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, to an evolutionary interpretation of some provisions of the European Convention. But even an ordinary interpretation of the right to an effective remedy and the prohibition of discrimination considering the object and purpose of the Convention cannot be fully effective without an intersectional approach. This blog symposium offers examples of how the jurisprudence of the Court could incorporate such intersectional approach. A promising future for one of the most important human rights courts worldwide and for the protection of the rights of individuals with intersectional identities, which most of us are.